When a borrower defaults on a multifamily income property loan, it is usually the culmination of a number of events and decisions over a period of months or even years. Once started down the default path, the end is very predictable. Ironically, lenders do a poor job of monitoring the progression, with the result that they can't accurately predict which loans will default.

The Slope

Stage 1 - Employment Downturn. Almost always, defaults occur when employment declines in a market. Obviously not all tenants depend on a job (retirees, students), but most tenants do, and when there is an employment downturn tenant turnover increases because tenants double up or relocate to better job markets. Also, tenant traffic decreases because fewer tenants are looking for housing. There is very little a borrower can do to stem turnover caused by economically distressed tenants or increase the number of tenants looking for housing.

Stage 2 - The Borrower Takes Productive or Counterproductive Steps to Increase Occupancy. To counteract increased turnover from economically distressed tenants, about the only productive response a borrower can make is to work harder to retain existng tenants. In a market where fewer tenants are looking for housing, the productive approach is to try to improve the project capture rate with more advertising and lower rents and/or concessions. There are a number of other things borrowers do (or don't do) which are counterproductive:

- Lower Tenant Quality Standards. One approach to increasing a project's capture rate is to accept tenants with poor credit or rental histories.

- Replace Capable Management. An owner may mistakely attribute the decline in occupancy to ineffective onsite or third party management. Obviously, an occupancy problem could be caused by ineffective management, but if the real cause is an employment downturn, blaming management will not help. In this circumstance the new management won't be more effective, and they could be worse.

- Do Nothing. This strategy might work if the economic downturn is short and shallow, but is not constructive in a prolonged downturn because other owners will adjust to the new market conditions, and the project owned by the do nothing borrower will become increasingly uncompetitive.

Stage 3 - Economic Distress. This stage could occur simultaneously with Stage 2, or may appear later. It occurs when the borrower doesn't have the funds to increase advertising and/or properly maintain the project and turn the units. If he or she hasn't already done so, the borrower may cut tenant qualification standards and/or replace mangement. Often borrowers who were using professional third party management fire the company and manage the

projects themselves at this stage.

Stage 4 - Cycle Intensification. At this stage the counterproductive actions the borrower has taken reinforce the cycle. The reduction in tenant qualification standards results in tenants more susceptible to economic distress themselves, and often make it more difficult to attract or retain better quality tenants. Good managers and management companies do not want to be associated with poorly maintained projects and leave. Good quality tenants leave the project because it is not being properly maintained, and it is very difficult to attract good quality

tenants to a poorly maintained project in a soft market. Eventually the project does not generate enough income to service the debt, the borrower exhausts his or her reserves, and there is a default.

Loan Rating and Watch List ImplicationsLenders attempt to anticipate defaults by using a loan rating system and a watch list of loans they believe are more likely to default. While this is obviously a good idea, lenders are often watching the wrong things:

- Market Rents and Vacancies. Rent and vacancy trends lag employment trends - by the time rents are declining and vacancies are increasing borrowers are already at Stage 2. It makes more sense to monitor employment trends as the initial trigger for concern.

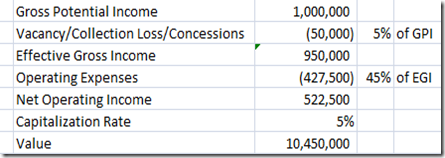

- Focus on Physical Occupancy Instead of Net Rental Income Trends. Often lenders will focus on physical occupancy as a watch list criterion. Although low physical occupancy obviously signals a problem, a project may be maintaining good physical occupancy by cutting tenant quality standards, lowering rents, and/or offering concessions. A much better indicator is change in net rental income from the previous period.

- Turnover. Although lenders usually get a rent roll at least annually as part of their monitoring process, they almost never look at a project's turnover (which is easily calculated by looking at the tenant move-in dates). A sharp increase in turnover is a good indicator of a potential problem.

- Debt Service Coverage. Most lenders are fixated on debt service coverage as their primary watch list indicator. While it certainly makes sense to watch DSC, it can't be done in isolation. In an economic downturn if a borrower is making productive responses expenses should go up (primarily in advertising and maintenance line items). A project and borrower in economic distress will show a decrease in expenses as maintenance and other costs are deferred. Paradoxically, a project with a low debt service coverage created in part by high advertising and maintenance expenses has a lower risk of default than a project with a better debt service coverage because the owner is deferring maintenance and other expenses.

- Property Condition. Most lenders monitor property condition with annual inspections, which is a good idea. However, there is almost never any continiuty in the inspection process - every year a different inspector looks at the property, so no one can say what the trend is until a project is in bad condition.

Initial Loan DecisionsThe slope model also has implications for the initial lending decision:

- Borrower Domicile. In my experience, borrowers who do not reside in the project's market (for example, a Los Angeles investor owns a project in Dallas) have a much higher default rate than borrowers who are close to the markets they invest in. Borrowers who are not close to their markets have difficulty taking early and appropriate steps at Stage 2 relative to local investors, which places their projects at a disadvantage.

- Borrower Experience. Similarly, inexperienced borrowers have more difficulty reacting appropriately at Stage 2, and have much higher default rates.

- Financially Weak Borrowers. Borrowers with limited net worth and liquidity are virtually always the first to default in a downturn, because they start out in Stage 3. Although most lenders consider experience and financial strength in their initial lending decisions, very few capture this information after the loan is approved and incorporate these factors in their loan ratings and portfolio analysis. I've never heard of a lender tracking borrower domicile as a risk factor.

10 Questions Income Property Lenders Should Ask Themselves

1. Do you know which loans in your portfolio are secured by properties whose owners live in a different market than the property?

2. Which loans in your portfolio have borrowers whose net worth is less than the loan amount and/or whose liquidity is less than 10% of the loan amount?

3. Can you say which properties in the portfolio experienced more than a 10% decline in net rental income from the last period?

4. Do you require the same inspector be used for project inspections from year to year?

5. Of the markets you lend in, which have experienced employment loss over the previous 12 months?

6. For properties with DSC ratios between 0.90 and 1.10, which are reporting maintenance expenses more than 20% less than originally underwritten?

7. How many properties in your portfolio have annual turnover rates higher than 70%?

8. Which properties replaced their management companies last year?

9. Which properties have moved from third party management to self management?

10. Which properties in your portfolio are owned by borrowers who have less than 100 units in that market?

Congratulate yourself if you can say yes to any of these questions; you are doing a better job of portfolio management than most. But, if you can't answer yes to all of them there is room for improvement in your monitoring procedures.